Pakistan — History Denied

- A Reawakening of Pakistan

- National Narratives – A Double-Edged Sword

- Indus Inland Waterways System

- More Provinces

- Muslim Monopoly on Suffering. A New Way Forward

- National Defense ReCalibration

- The Foolishness of Conspiracy Theories

- Ijtihad

- Emigrant Literati and the Criticism of Pakistan

- Pakistan — History Denied

The history of pre-independence Pakistan has often suffered at the hand of nationalist historiographies. Vested interest groups including Pakistan’s Islamic-oriented establishment, India’s Hindu nationalists, European colonizers, and Orientalist academics have often minimized the importance of Pakistan’s distinctness and oneness within South Asia. Each had their own motive for doing so. The British needed to paint “India” as a timeless, unchanging land in need of British progress. United India’s proponents need to insist upon a united, rarely interrupted, antiquity. There are those that wish to discredit the country by making it appear an artificial, last-minute concoction. Salman Rushdie has said Pakistan was “insufficiently imagined”. There are others who insist Pakistan be relegated to an asterisk in the larger “Indian” History. To Hindu nationalists, in neighboring India, Pakistan is a secessionist province of Akhand Bharat (Greater Bharat). Its existence separate from present-day India is an anomaly that will be reversed at some point in the future. Western scholars have packaged all of South Asia, a landmass larger than all of Europe, into an all-encompassing “Indian” subcontinent. In this orientalist perspective, northwestern South Asia is indistinct from the rest of Gangetic and Peninsular India. Pakistan’s response to these narratives has been to over-compensate with a fictitious counter-narrative about Arab ancestry. Instead of facts, each interest group has attempted to impose their version of the truth on this land and its gallant people. The study of this area as a distinct region has been underserved relative to the great acts of human drama that have unfolded in its bosom.

Table of Contents

Akhand Bharat

Indian nationalists have insisted on a united antiquity. (Metcalf & Metcalf, 2011) For example, there is the historiography of “Akhand Bharat” or greater Bharat. According to its adherents, there has been a unified and continuous country “Bharat” since time immemorial and all of South Asia is a part of this larger entity. According to this theory, the modern-day Republic of India is the successor state to Akhand Bharat while Pakistan and Bangladesh are merely its “secessionist provinces”. In some commentaries, this mythical India lays claim to land from Afghanistan to Burma and Nepal to Sri Lanka. Astonishingly, it sometimes even includes Malaysia, Thailand, Burma and Vietnam! (Puniyani, 2005)

The unified state theory continues to find its most ardent supporters amongst patriotic Indian and Hindu nationalists. Many continue to harbor the sentiment that Pakistan is a breakaway province of Bharat Mata (Mother India). Typical of this attitude is the one exemplified by Indian Justice, Markandey Katju, who has written to Pakistani newspaper editors on this very topic. Mr. Katju has confidently declared “there is no such thing as Pakistan; there is Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan and North West Frontier Province, all of which are really part of India… There is no question of bringing two countries together when there is, in fact, a single country, India. Pakistan is a fake country, artificially created by the British in pursuance of their nefarious policy of divide and rule.” (Katju, 2013) Paradoxically, this logic can be used to infer there is no Republic of India either; there is only Nagaland, Orissa, Kashmir, etc. We can further expose this fallacy by asking a rhetorical question: Why does Punjab only cease to become a “thing” when it is absorbed into the Republic of India? The truth is that every nation-state is a political construct yet opinions like the one espoused by Mr. Katju, conveniently single out Pakistan for its alleged artificiality.

Ram Madhav, no less than the General Secretary of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of India’s ruling party claims “the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (spiritual and ideological head of the BJP) still believes that one day these parts (Pakistan and Bangladesh), which have for historical reasons separated only 60 years ago, will again, through popular goodwill, come together and Akhand Bharat will be created, As an RSS member, I also hold on to that view.” Even mild-mannered, secularists such as the first prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, have relegated Pakistan to a footnote of the larger “Indian” history. Nehru considered Pakistan’s “separation” from the newly formed Republic of India an anomaly that would be reversed in “five to ten years”. It should be noted that other highly respected Indians such as Dr. Ambredkar and Rabindranath Tagore have dissented on the question of a one-nation India.

Pakistan has been grouped into this mythical India in the popular imagination. This is partially due to Pakistan’s last pre-association with British India prior to independence. However, this association and its inferred permanency is a mirage. British India was not one country but rather an amalgamation of states coerced, conquered, and consolidated into a whole. Burma, Sikkim, Ceylon were part of British “India” but not anymore. The simple fact is that a unified, united, or monolithic subcontinental state has never existed. The near exceptions were territorial due in large part to the application of brute force by three major empires: Mauryas, Mughals, and the British Raj.

To illustrate the fallacy of the unified state theory, we compiled dozens of historical maps of South Asia from the bronze age to the present and recorded our observations in a database. The reader can peruse this data here. The result of this research unequivocally proves South Asia has always consisted of multiple nations and kingdoms usually exchanging kings and empires in roughly the same regional and cultural zones. We can confidently draw the following conclusions:

- The entire landmass of South Asia has never been one unified state nor a monolithic culture or civilization.

- South Asia has always consisted of multiple regional and cultural zones.

- The Indus region of present-day Pakistan, whether united or divided, was separate from the Gangetic and Peninsular zones of present-day India for approximately 9,000 out of 10,000 years.

To demonstrate these 3 points, let us examine the year 625 B.C. as a randomly selected data point. The following tables show the various kingdoms that existed in 625 B.C. and their location in respect to present-day countries of Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, India, and Sri Lanka.

| Ancient Kingdom | AFG | IRN | PAK | IND | SRI |

| Kashi | X | ||||

| Kerala | X | ||||

| Kukura | X | X | |||

| Kundivrsa | X | ||||

| Kuntala | X | ||||

| Magadha | X | ||||

| Matsya | X | X | |||

| Mulaka | X | ||||

| Panchala | X | ||||

| Pandya | X | ||||

| Shabara | X | ||||

| Surasena | X | ||||

| Surashtra | X | ||||

| Vatsa | X | ||||

| Vidarbha | X | ||||

| Archosia | X | X | |||

| Barbara | X | ||||

| Gedrosia | X | X | |||

| Gandhara | X | X | |||

| Kuru | X | ||||

| Kabul | X | ||||

| Medes | X | ||||

| Sauvira | X | ||||

| Persia | X | ||||

| Anuradhapuran | X |

The 625 B.C. data point shows no less than twenty independent kingdoms in South Asia, fifteen in present-day India, and eight in present-day Pakistan. Two kingdoms were shared between Pakistan and India. Pakistan shared kingdoms with India, Iran, and Afghanistan. This is just one data point. The aforementioned patterns 1-3 repeat over and over again. The one difference being the Pakistani region was typically part of the same kingdom or empire, while the much larger Gangetic and Peninsular India was part of many kingdoms or empires. In short, there is no such thing as a monolithic country of India. The three major empires of the Maurya, Mughals, and British Raj were the exceptions rather than the rule. In essence, the term “Indian subcontinent” is an anachronistic term of European colonizers. No serious geographer can consider the region of Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka as anything other than the South Asian subcontinent.

Occidental Orientalism

Other, less accomplished critics are simply ignorant of region-specific histories of this vast subcontinent. Some British observers of the colonial era suffered from an orientalist perspective from which northwestern South Asia may very well seem entirely indistinct from Gangetic or Peninsular India. British cartographers coined the term “Indian Subcontinent” for a landmass larger than the “whole” continent of Europe. The last Viceroy of British India, Louis Mountbatten, a man of very little knowledge of the colony he oversaw, remarked “as far as Pakistan is concerned, we have put up a tent … it will collapse soon.” The tent however has outlasted many of its doomsayers precisely because of its historical logic.

Historians and cartographers have all too often packaged all of South Asia into an all-encompassing “Indian” subcontinent. This geographical designation gives the impression that the diverse cultural and political zones of South Asia are merely a part of a monolithic “Indian” whole. The term “Indian Subcontinent” is a misnomer. Nobody refers to all of Western Europe as the French Subcontinent. Such an absurd designation would most certainly minimize the historical significance of other nationalities such as Holland, Belgium, etc. Similarly, the “Indian Subcontinent” has many cultural zones, some with a geopolitical continuity that is older than the nationalities of Western Europe.

- South Asia has more languages than Europe.

- South has more diverse physical characteristics than Europe.

- South Asia has more diverse landscapes (desert, jungle, mountain, plains, deltas)

Etymological Confusion

The term “Indian Subcontinent” is a misnomer on several levels. The British cartographers who coined this term with a “sub” prefix failed to appreciate that the landmass and cultural, ethnolinguistic diversity of this area was greater than the “whole” continent of Europe. Secondly, the term assigns the name of a part of the region to the whole. The very name “India” represents the region of the Indus Valley which was understood to be the easternmost country of the Persian Empire. For Herodotus, the Greek Historian, “Indos” bears this original meaning. In later documents, Greeks and Romans transferred the best-known country of Indus to the whole of South Asia thus setting an example that has been followed to this day. (Rapson). Thirdly, the term “India” is a mispronunciation of mispronunciations. At the time of Alexander the Great’s invasion of northwestern South Asia, the Sindhis called their river Sindh. The Greeks understood it to be “Sinthos” which later became “Indos”. The Arabs and the Persians pronounced it as “Hind”. The Europeans made it India. This series of misappropriations and mispronunciations have had some interesting geographical consequences. Followers of one of the great religions of Hinduism owe their name to the river Indus. Had they chosen a name of their own, it would perhaps be named after the Hindu heartland of the Ganges or the Brahmaputra and not the Indus. When the people of South Asia broke the yoke of European colonialism, the dominion of peninsular South Asia chose “India” as their name instead of Hind, Bharat[1], or Hindustan. As a result, the Republic of India does not actually include the “Indus” country.

Al-Bakistan

Pakistan for its part has bristled at any hint of criticism regarding its statehood. Insecure since birth due to multi-pronged attacks to its viability, Pakistan’s reaction has been predictably counter-productive. The country’s establishment has propagated a defensive counter-narrative, through state media and the academic curriculum of “Pakistani Studies”. The state narrative has focused exclusively on Pakistan’s illustrious Islamic history while willfully ignoring its illustrious pre-Islamic history. Pakistani prejudice towards all things non-Islamic, Muslim interpretation of jahiliya, and a misguided state policy has resulted in a sort of collective amnesia of events and history prior to the Arab invasion of Sindh. Even today, some Pakistanis hold the absurd belief that Arab general, Muhammad ibn Qasim, was the “first Pakistani”.

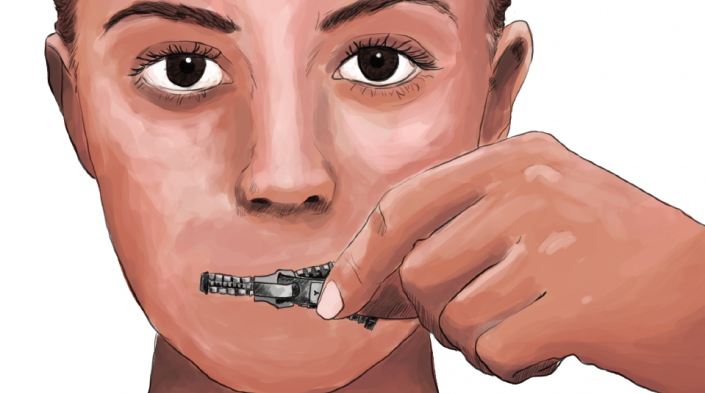

Al-Bakistan is a state of self-imposed selective amnesia of pre-Islamic history. One of the most shameful elements of “Al-Bakistan” is the revulsion to anything that may be considered “Hindu”. Therefore, even if it was the inhabitants of the Indusland who may have passed on the Hindu numerals to the Arabs, Pakistani tend to take pride in the Algebra and Trigonometry of the Arabs more so than their own contribution. This most unfortunate imbalance is rooted in the deep Muslim/Hindu communalism embedded and Pakistan’s very bloody separation from British India. It is a sincere hope that the facts in this book should provide for a more nuanced understanding of Pakistan’s diverse makeup. Hence where Akhand Bharat does not admit distinctness, Al-Bakistan does not allow for commonality. Both positions are equally

Internet Ad Hominem

Ostensibly, the establishment emphasized Pakistan’s Islamic orientation over other dimensions to counter the historiographical hegemony of a predominantly Hindu India.[2] However, this policy has only managed to strengthen the position of those that wish to deny, disparage or denigrate Pakistan. For example, a particularly crass narrative about Pakistani ancestry is the one peddled by hawkish and multitudinous Indian commentators; According to this narrative, Pakistanis are the product of Muslim rapists and Hindu out-castes. (Shah, 2012) Thus the Pakistani is the traitorous progeny of a barbarian father and an “unworthy” native mother. While such inflammatory and dehumanizing generalizations are patently false, a lack of self-knowledge about Pakistan’s pre-Islamic past thanks to an equally ridiculous Pakistani version of the “truth” has left ordinary Pakistanis poorly equipped to counter such allegations. Furthermore, attacks on heritage and history are then extended to Pakistan’s very statehood and viability.

Wikipedia Vigilantism

To illustrate just one of countless examples of misappropriating of history. At a website called “Maps of India”, the Indus valley civilization is described in the following manner: “The earlier part of the Indus Valley Civilization, which is even (sic) known as the Mohenjodaro – Harappa Civilization dating back to 3300 BC marks the beginning of the Bronze Age. Originating from the banks of the river Indus and its tributaries, primarily, the civilization was located in the present-day Gujarat, Haryana, Rajasthan and Punjab states of India and some parts of Pakistan. (http://www.mapsofindia.com/history/ancient-india.htm) To relegate IVC to just some parts of Pakistan is not just revisionist history, it is an outright lie. India archaeologists and anthropologists are changing the name of Harrapan civilizaton to Sarasvati civilization. As usual, Pakistani intellectuals are too busy either self-flagellating, Pakistani academics are fabricating, Pakistani conservatives are ignoring.

Expatriate Literati

Not all rejectionists of Pak history are far-right Indian nationalists or aspirants of Akhand Bharat. There are other influential critics that agree with Indian nationalists but for different reasons. Some hold an unflattering opinion of Pakistan due to their ideological beliefs. This includes distinguished intellectuals of atheist or Marxist persuasion for whom a capitalistic country founded on the basis of “religious nationalism” is an anathema. Christopher Hitchens’ diatribe in Vanity Fair describes Pakistan as “virtually barren of achievements and historically based on the amputation and mutilation of India in 1947”. (Never mind for a moment that Pakistan produced a Nobel prize in Physics within a few years of its existence!) Other critics discredit Pakistan’s formation by characterizing it as an accidental, last-minute concoction. Tariq Ali in his book “Clash of Fundamentalisms”, compares Pakistan’s birth to a cesarean section surgery. Salman Rushdie calls Pakistan “insufficiently imagined”. Pakistani intellectual Ayesha Jalal calls Pakistan’s creation a “colossal mistake”.

The Pakistani establishment’s distortion of history along with a poorly educated populace has played into yet another popular criticism regarding Pakistan, its so-called “identity crisis”. Once again, it is the distinguished expatriate literati such as Zahid Hussain, Ahmed Rashid, Hussain Haqqani, Tariq Ali, Ayesha Jalal with a pessimistic outlook and a fatalist prognosis. According to the identity crisis theory, many of the ills that plague Pakistan including economic malaise, poor social development, its alleged obsession with India, sectarian divisions, military dictatorships, and Islamic extremism are all related to a confused sense of self. If the pessimism emanating from the hallowed halls of Oxford and Harvard are to be believed then gaining a solid understanding of Pakistan’s history becomes imperative. If we are to address our “identity deficit”, we need to correct our “memory deficit”.

[1] Bharat is one of the official names for the Republic of India.

[2] Some revisionists are suggesting that the IVC religion was a Hindu civilization or that the Harrapan civilization should be renamed to “Sindhu Saraswathi Civilization”. Example: http://www.hinduwebsite.com/history/indus.asp